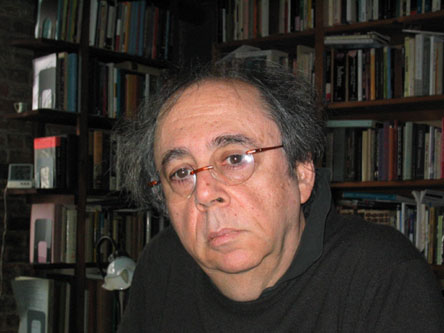

Richard Foreman Interview

February 7, 2003

NF: Your first theater was attached to the

alternative film scene that was going on at the Cinematheque

building.

RF: My first theater was given to me by

Jonas Mekas when they closed down at 80 Wooster Street. He had a film

theater but the fire department closed it down. He didn’t have a license

to show films. So he said to me, “Well, we can’t show films, but they

didn’t say anything about plays. So why don’t you take it over and do your

plays.” So for three years I had that space rent free to do

plays.

NF: So that’s how you got

started.

RF: Yes. Well, I had gone to

school. I had been a member of New Dramatists, a member of the Actors

Studio Playwrights Unit. But I didn’t have any credentials. I did

write one play when I got out of Yale that actually got optioned for Broadway by

this rich lady, but nothing came of it finally. Then I started because I

saw these underground films and that inspired me to rethink everything that I

was doing in theater.

NF: Specifically, like the film “Flaming

Creatures”?

RF: Oh a lot of things, “Flaming Creatures,”

the films of Michael Snow, “Wavelengths,” a lot of people. For about five

years, I and my first wife would go to screenings literally every single

night. So that was our world for three or four years. And she became

a film critic.

NF: That must have been in the late

sixties.

RF: Well, in the mid-sixties.

NF: So you’ve been doing plays ever since,

once a year?

RF: Well, I started doing plays in

’68. And in those days, for the first 15 years or so, I would do two or

three plays a year. I would also do plays for other producers and so

forth. At a certain point, my second wife, Kate, who was the leading

actress in my theater for about 15 years, got very very sick. And she

didn’t want to act anymore anyway. So it became, and still is, very

difficult for me to leave New York for extended periods of time. Now I

can’t go around the world doing plays as I used to. And Joe Papp died, and

he used to ask me to do plays from the classical repertoire. So I’ve

fallen out of that world. I occasionally do other things – I have some

other plans — but I can’t be as active as I used to be.

NF: What for you has changed over the

years? America, in the mid-sixties, was the center of a

counterculture. Now, thirty years later, America represents a dominant

culture.

RF: Oh yes. Well, I grew up in the

fifties. And I grew up sort of hating America. I went to Europe for the

first time when I graduated from college and it was a total revelation. For

about 10 or 15 years, France was the great love of my life. And then I

went and did with Kate about 7 or 8 productions in Paris, because Kate grew up

in France. Her father was a translator and during the McCarthy era he went

to live in France and never came back. Kate didn’t come to America until

she was 26. So I almost moved permanently to France. But I then finally

realized I was an American and I had to fight my battles here. So during

the 60s was the only time that I felt good about America. I and my friends

really believed the world was totally changing. Then, beginning in the

80s, everybody started glorifying the 50s again which was horrendous. And

now I feel as alienated from America as I ever have. And I find it very

difficult now. I mean, I am sort of established now, so I get a miniscule

amount of funding that allows me to do my plays every year. But I feel

very adrift. I feel that the arena, the context in which I do my work had

dissolved, is meaningless. I really don’t know anymore for whom I’m doing

this work. I used to sustain the illusion that I was participating in a

dialogue with the whole tradition of Western culture — serious, modernist,

Western hard avant garde culture. I deeply sense that that possibility

does not exist. We live in a corporate world of the bottom line, and I

think that deeply affects everybody’s psychology, everyone’s mentality. I

do these plays and I don’t know why I’m doing them. But I’m very unhappy

about being here and doing them in the context that I’m doing them. But I

can’t figure out what else to do.

NF: Are they in a way a counter to the

dominant culture?

RF: Well, I’ve always made a work of art

into which I could disappear, but it gets harder and harder to sustain that

illusion. In the last two years also, the audience, I must admit, is

less. I can’t quite figure out why. I just don’t know. In a

sense, I would like to do more radical, but admittedly, modernist work.

Modernist work belongs to the past. We’re obviously moving into something

else. In a way I feel slightly guilty for making my own contribution to a

kind of disassociated, super-fast, super-complex art that, in a sense, has led

to MTV and all kinds of things I don’t really approve of. But I see how

there are certain suggestions of that in my work. So I’m totally confused

about that.

NF: You’re a theater artist who, more than

most today, have continually studied, pondered and disrupted “process” — whether

it’s the process of writing or the process of staging theater. Where are

you now with that? I imagine you’re still doing that.

RF: Yes, but as you get older, it’s harder

and harder to do it. Like, every year I think, “oh, in this one I’m going

to trash everything I’ve done, make it totally different.” And I start out

that way, but then it doesn’t reverberate in my soul in the right way. So,

whereas each year I think I’m going to take a six-foot step forward, as I’m

working on it, in order for it to seem emotionally correct to me, it ends up I

think being a one-foot step forward. Maybe that’s not a bad way to

proceed. What people are doing now involves a lot of media, a lot of

technological stuff. I find it very hard to get into that area. It

does not seem to me to speak to the notion of the complexity of the human soul

that I inherit from the modernist period, the modernist orientation. I

think we’re producing a race of people who are paper-thin – almost pancake

people – who cover a lot of territory. Like the Internet. And our

psyches cover a lot of territory, but to me it’s sort of pancake-thin.

That may in the end produce something totally different, and totally interesting

and totally justifiable. And I have certainly dabbled in that. And I

have my tendencies to that. But in the end I still have a spiritual center

that I find hard to deny and hard to have my work deny.

NF: You’ve referenced alchemy in talking

about your process. Seeing the staging of your work reminds me of an

alchemist laboratory perhaps — the different props and scenery. I wonder

if you could talk about that.

RF: I don’t think about that much

anymore. It was very influential upon me when I started my work, in ’68 or

so. I was reading books about alchemy, about techniques, and down through

the years when I feel dry, when I need some inspiration, I’ll often go back and

look at some of the illustrations of those old texts to get ideas. But

these days there’s so much that I’ve been through intellectually, and that is

part of the past – it’s not something I think about these days — but I can

clearly see that is one of the strong sources of my beginnings and it still

influences me.

NF: You have two different processes,

directing and writing. Do you put a limitation on either of those – either

in time or ambition?

RF: Well, there’s been a change in

trajectory. I began as a writer. Well, when I was a kid I began

making scenery for local high school productions. And I went to Brown as

an actor. But I started writing plays because my friends were and I thought I

could do it well. So I then went to Yale Drama School as a writer.

And I think of myself as a writer. I only started directing plays because

nobody else would do my plays. As a writer when I began in the 60’s I

wanted to start from scratch. I hated the manipulative kind of playwriting

that was American playwriting in those days. So I pared down the language

and I wrote plays that only registered the kind of physiological things going on

in the body in very primitive language. Then I began to feel that I wanted

my writing to be richer. So, somewhat under the influence of back in the

early ‘70s reading Barthes and some of the other French theorists, my work

became verbally much more complex. And all these people were saying,

“Well, Foreman’s a pretty good director but the texts, they could be the kitchen

sink, they could be the telephone book.” And I always thought that wasn’t

true. I thought that I was a good writer and that I was basically a

writer. So I consciously sort of wanted to prove that I could write.

And my texts became much more complex, much more multi-layered, much more

aphoristic. And I think I finally proved to the world that I could write,

because I started getting awards as a writer. And about 2 or 3 years ago,

I started getting disgusted with writing, feeling that good writing was almost,

in Barthes original terms, writing that belonged to a political class, made

certain political manipulations. And I got sick of writing well.

There was so much good writing that I admired in my life and that I had tried to

do and it no longer did it for me. So two years ago I started doing some

plays in which there was very little writing, just aphoristic phrases coming

over the loudspeakers – maybe 40 or 50 sentences in the whole play. I’ve

done that for 2 years, started to branch out a little, and starting next year I

may return to writing, but that’s the arch that I’ve gone through. Who

knows. So the writing always comes first. I amass these texts.

They’re written at random moments. Pages from different years, different

months, are combined in various ways. I then go into rehearsal with these

texts. And nowadays I rewrite a lot as I think I’m going into rehearsal.

In the 80’s I didn’t rewrite a word. I felt sort of like Kerouac:

What comes is the evidence of your spiritual state and you musn’t touch it; you

must confront what’s come out of you. Then I started rewriting. I rewrite

now a great deal in rehearsal also. I have no hesitation about doing major

rewrites in rehearsal in response to what I hear the actors doing, what seem to

be the actors’ strengths. So the plays are now half written in rehearsal

even though I always go into rehearsal with finished texts. I always felt

that I had more courage as a writer than as a director and that as a director I

was a little bit reactionary because I was concerned with trying to make these

massive, impressive machines; whereas as a writer, I was open to letting come

whatever crazy impulse would come. It’s also very hard for me as a

director to stand in front of a group of 20 people and act as stupid and as

empty and as not knowing as I can do as a writer. Faced with all those

people, my personality is such that I want them to think I’m in charge that I

know what I’m doing. And I look upon that as a mixed blessing. I

think there are problems.

NF: In your current play “Panic” you’re

sitting in the audience with your sound board directly involved in the pace of

it.

RF: I’ve done that from the

beginning.

NF: Sitting in the audience?

RF: Sometimes sitting in the back. It

depends on the play and where I feel I can experience what I have to

experience.

NF: It was very interesting. I was

sitting right next to you, and because of the lighting on the audience and other

alienating techniques, as an audience member I was not only conscious that I am

“watching a play” but also that the playwright/director is also an audience

member sitting next to me, whose recorded voice occasionally comes out over the

loudspeaker.

RF: In the early days, I even used to – 50

times throughout the performance – and in those days sitting in the front of the

audience – shout out, “Cue! Cue!” to make people do different

things.

NF: You’re just one degree removed from

being an actor in the play. So as a theater artist, you are a playwright,

director, designer, theorist and actor of your plays and productions. Is

there any hierarchy in that? I’m interested in how you think the history

of theater is passed on from generation to generation and how you fit into that

history of theater.

RF: I have no idea (laughs). I always

had a love-hate relationship with the theater. I got into the theater as a

young kid because I was very shy. It was a way to live out a fantasy life,

to relate to people, that I couldn’t do in real live. So at a very early

stage I began to find the theater not very interesting and the other arts, other

disciplines, always much more interesting. After the initial phase of

responding to the glamour of the theater, I began to use the theater much more

consciously as a kind of therapy, therapy for myself and therapy for those

members of the audience who wanted to engage in this process of trying to

perceive at a slightly different rhythm – trying to process ones perceptions at

a slightly different rhythm. And to me, I think that’s what I’m

doing. So it’s therapy, not so much in a psychological sense but more like

somebody’s meditative practice (laughs).

NF: I’m reminded when I first started

reading Gertrude Stein years ago, the initial frustration and finally the

understanding that it wasn’t reading in the normal sense. It became more a

meditation on the act of reading.

RF: Right.

NF: I have a similar feeling when I see your

plays. I’m so conscious of watching myself watching, watching others

watching the play. What’s left after you and I and the audience leave your

play? Going back to Gertrude Stein, the act of reading there, was the act

of meditating on one’s life also – moment to moment applying it to the reality

of one’s emotional or psychic life. So what’s left when we leave one of your

plays?

RF: I can’t answer that. I make

something that I need. I find life not very satisfactory. I find the

world we live in not very satisfactory. And I make paradise for

myself. I make the world the way I want it to be. And that world has

something to do with some concrete objects being there in the present, the way

your consciousness is dealing with it, the way you are handling what in the

present moment you are given. And there is a certain activity in the

present moment that I want to be able to perform that the life within which I

live, in the 21st century of America, does not provide. So I

make something that I’m desperately hungry for. Having made it, I guess I

can only hope that it stands as an example of some alternative possibility that

might to some people seem denser, richer, more interesting, more desirable and

then they make of it what they will. I work totally out of instinct, even

though after the fact I theorize a lot, try to help people understand what I’m

doing or where I’m coming from. None of that informs the work. What

informs the work is a feeling in my solar plexus and just continually saying,

no, that’s not dense enough, that’s not clear enough, just keep changing it

until something clicks and I can’t really say what it is, even though because I

read a lot, I’m then able to relate it to a lot of intellectual traditions, but

that’s after the fact.

NF: If we think of a certain theater

tradition in the last century that starts with Jarry and moves, say, through

Artaud, through you and now into the next century. Let’s say Artaud was

the big disruption. Many times people put Grotowski or the Living Theatre

as the inheritors of this tradition that’s come through Artaud but have left you

out. Could you speak to that?

RF: Again, that’s hard. I rarely think

of my work in terms of theatrical tradition. I think of my work in terms

of other philosophical, poetic, spiritual traditions. Now I can see a

certain relationship to certain things in Artaud. I read Artaud back in

school in the late ‘50s early ‘60s and certainly I responded to certain levels

of it. And I occasionally look at Artaud again. I think that, by the

way, the Living Theatre manifested Artaud back when they were doing things like

“The Brig” and “The Connection” way back then. I don’t think they were

manifesting it later in their more popular period, when they came back from

Europe and did all those things. Now, Grotowski is not somebody that I

respond to at all. I think that at the beginning of my career indeed I

said that what I wanted to do was “Artaud in the Bronx,” in other words, Artaud

in terms of bourgeois living room settings – that the cruelty of life is in

these little moments of awkwardness and stumbling, and miscommunication that are

also openings to a whole other world, not just symbols of our isolation as they

are in something like Chekhov or Pinter, but are really opportunities to see a

cosmic energy pouring through which is why Ontological is one of the two names

of my theater. So, for years, when I was a young man, I thought I wanted

to be like Artaud, but I thought, “yeah, but I don’t want to end up crazy and

committed ” (laughs). And I have a little problem with Artaud, the

glorification of Artaud, because it’s the glorification of a man who was

insane. And I don’t say that in a negative sense (laughs). He was

also in touch with energies that very few other people were in touch with.

But a lot of times the promoters of our Artaud forget “but at what cost? At what

cost?” So how does one who does not want to be that troubled make contact

with similar energies? That’s the real problem.

NF: It seems like in this play you’re moving

towards an exploration of death.

RF: Yes, I think so. But I always have

been.

NF: Does that have anything to do with

age?

RF: No. I’m 65 now. But death

certainly has been featured in my plays. I think almost the whole

time. Twenty years ago I started saying that the basic theme of the

theater was death. I thought the theater was death — it wouldn’t be in

Artaud’s theater – but any theater like mine, which is most theater, where

things are repeated night after night, you shun death somehow. And for 20

years my work always featured a lot of skulls and that has been an obsessive

theme in my theater I guess.

NF: You use both actors and

non-actors.

RF: These days I use actors. I used

non-actors in the beginning, but I haven’t for quite a while.

NF: What are you looking for in an actor

that another director might not be looking for?

RF: I always hated actors basically, in the

sense that most actors, understandably, want to be loved. I want

performers who are willing to withhold themselves. I was very influenced

in the beginning by Bresson’s use of actors in films, where he asked people – he

used non actors – and he wanted to use them as models he used to say, because he

didn’t want them to try to manipulate the audience, try to develop empathy with

the audience. And that’s always been my tendency because I want to make

something confrontational. And I hated this American theater where we’re

all supposed to be friendly and, in a very superficial way, to look into each

other’s eyes and say, “hey, I like you” basically (laughs). No, I want to

be challenged by people, I want to be awakened by somebody who looks at me and

says, “I see through your shit.” (laughs). I mean I don’t say I want it

because it’s tough. It’s tough. But in making art, it’s that kind of

feeling that I want from the performer. I don’t want that kind of desire

for puppy love which I think is at the root of the actor’s craft. I also

don’t want, like Grotowski, a release into a kind of organic body of orgasm that

suggests a sensory, sensual way that the audience can identify with that kind of

release. Because that is escaping for me also the real problem, whatever

that is. The fact that you have to share this planet with other people

that have minds that function much like yours. Yet you want to maintain

your individuality and that person sitting across from you, basically, when it

comes down to it, wants your food, wants your air (laughs). You are

constituted as a human being to wants your own food, your own air, even though

your mind probably is going through many similar processes and you may share on

some level the same mental consciousness. And it’s that kind of

problematic that I’m interested in. So I want actors who can suggest the

intensity of that problematic.

NF: There’s a sense of almost evil innocence

on your stage, as if bad kids are playing at this forbidden game and then

staring back at their parents insolently saying, “I’ll do whatever I

want.”

RF: I think we’re all kids. I have

known very few adults in my life. (laughs)

NF: Getting back to the actor/non-actor

thing, for a long time in your career you did work with non-actors. Now you’re

working with actors but you’re asking these actors – I talked with Elina before

coming here – basically to be in service of a painting you’re making on

stage.

RF: The compositional reality would be the

big reality. I was going to mention Elina because she said during

rehearsal, “This is the hardest thing I’ve ever done, because you want to take

everything away from me. You want me essentially to become a

non-actor.” And I do in a sense. I do in a sense. I do want

something real to be going on. I want some real energy, a real commitment

to be there. But I don’t want any of the normal rhetorical emotional

tricks that the actor grows up learning and using.

NF: When do props in your plays go to then

next level of becoming something else, talismans maybe? You have a tomb on

stage for instance and a phallic thing suggesting maybe two poles within the

play. When are these props or talismans brought in? Before you begin

your rehearsal?

RF: I have a script which essentially I

write and rewrite listening to some music trying to get it right in my

head. Then I design a set and I look at the script. And — in about an hour

– for every page, I read the text very casually and I get some ideas for some

props. Just pop into my head from nowhere. I just jot them down and I end

up with a list of like 50 props. Then I go through the play one or two

other times, again thinking about it and throwing some of those things out and

getting a few other ideas. But then we make those props. Then in

rehearsal – we rehearsed for 14 weeks this last time – props get thrown out,

changed. The prop guy – this year we had a student form down south making

my props – he was going crazy: “My god, I worked for 2 weeks making this

beautiful thing and then he throws it out, it doesn’t work and instead he wants

this.” So again, it’s all intuitive. I have no answer.

NF: I have a designer friend who worked with

you twelve years ago on “Eddie Goes to Poetry City.” She said she worked

real hard on this detailed poster you had her make. She brought it in to

you and you cut it into a bunch of pieces, Xeroxed it and pasted it all over the

set.

RF: (laughs)

NF: You must often run into some

resistance. Well, the people are there to work with you, but they must

constantly question you on what you are really looking for. You continually

disrupt the creation of the product to bring everything back to the

process. It seems that if you had unlimited time that you would

continually cut out what’s funny or what “works” – that you would keep the

process open and never get to a finished production.

RF: No. I wouldn’t. I

wouldn’t. It’s hard to explain to somebody else. But I’m waiting for

a certain click that it seems right to me – that it has the right density, that

it goes in seven different directions at once and yet still seems clear – I’m

waiting for that. And I’ve tried to build for myself this situation where

I can work the way that I work, continually trashing things. Now I don’t

throw out things that work. Now, I throw out things that seem

one-dimensional, or too simple minded or too easy. And I trash my own

material as much as I trash things that other people do. I’m constantly

saying, “Oh my god, that line of dialogue is stupid, throw it out; this staging,

this scene, throw it out.” Other people are saying, “Oh this is going

pretty well; this big dance number it’s good.” No. I just know it’s

not good enough. It’s not quite sharp enough. I also used to work in

situations – and still do occasionally – where I don’t have 14 weeks. Not

for my own work. But if I do other people’s plays? Yeah, I can do a

play in 4 weeks like everybody else. But to me, that does not allow the

uncovering of the real gold that is hidden somewhere in this stuff.

NF: Towards the beginning of the interview,

you said we are producing a race of people who are paper thin – pancake

people. What can theater do to counteract that? Of course, you’re

going to try to do that. But what are some projections you might have of

where theater could go?

RF: I have no idea. I’m waiting for

somebody to show me. I’ve been claiming I want to get out of the theater

for the last 15 years, believe me. But I don’t know what else to do.

And I need it. I just psychologically need it. But I have no

clue. I feel very much at sea. I still can make this little islands

for myself, and I was very happy making this play this year. I was less

happy when we opened and we had to worry about audience and so forth, but it is

still totally satisfying to me to make these works of art. That’s not to

say that there aren’t frustrating moments in making it, but I can always sort of

blindly forge ahead into the unknown. I don’t know. I’m always

waiting to see what someone else might do. I haven’t seen anything that I

really believe is a tremendous breakthrough to the next step. Not that I

go to the theater very much. But I’m aware of what people are talking

about, the current explorations. I’m always looking for things. Like

in the last year I discovered a filmmaker who blows me away. But it’s not

the next step. He’s 92 or 94 years old – this Portuguese filmmaker Manoel

de Oliveira, one of the great artists of our time that I didn’t know about until

about a year ago. But that’s not the future I guess (laughs), although I

don’t know; I don’t know. So I really don’t know. People my age

rarely know.

NF: What do mean by that?

RF: Picasso put down all the abstract

expressionists. Most artists reach a certain point where they can’t really

understand what is alive and productive in the work of younger artists.

That doesn’t seem to belong to their world; that doesn’t seem relevant.

But it might turn out to be the important thing.

NF: Did Elina give you that little book by

Genet [“What Remains of a Rembrandt Torn into Four Equal Pieces and Flushed Down

the Toilet”]

RF: Yes

NF: I found that interesting. I read

it thinking of your work.

RF: I found it very interesting.

NF: What remains of your work after it has

been cut into four equal pieces and flushed down the toilet? I think what

Genet was getting at is that there was a change going on in Rembrandt as a

person, a spiritual change, that brought him almost full circle to a child

again. Everything superfluous in his personality was gone. Rembrandt

was merely at the end of his life, a hand and an eye moving back and forth

between the paint and the canvas. Has there been an inner journey within

you that is not reflected necessarily in your work unless we look at it as

closely as you look at it?

RF: Yes. Yes. I think it’s easier for

a painter who does not have to deal with a mass audience. Because even if

I don’t have thousands of people in my theater, I’m still dealing with groups of

people. That makes it hard. There’s no question, when I started I

thought of myself as very cerebral, making intellectual theater. At about

40, I read Jung, who said that when you get about 40 there’s a big choice.

You either become a dried up, scholastic, bitter man, or you make contact with

some other river of feelings that is there to pick up upon. And I said,

“well, I don’t want to be one of those bitter, dried up men. I’m going to

recontact some kind of archetypal, mythical source.” And I did that sort

of consciously. I think that has informed my life. I think, however,

there has been a current in my work that is terribly humanist, terribly poignant

in dealing with the issue of death, in dealing with the issue of the childish

aggressiveness in all of us that is just a hunger for meaning, for love, what

have you. I’ve already expressed my frustration about being in the arena of

current times. I feel tremendous frustration of not being able to, I

suppose, have the courage to make plays that would be as minimal and as true to

a certain kind of maturity in older age, as somebody like Beckett did.

Now, I’m not a tremendous admirer of Beckett. But I’m a tremendous admirer

of the fact that he did exactly what he wanted to do. And if he wanted to

make a ten-minute play with just a mouth, he would do it. Now I’m corrupt

enough, that I find it difficult to entertain the notion of making that kind of

totally abstract theater that just says the one thing nakedly that I want to

say. Because I think, What’s the point? I would only be talking to a

few converted people and the activity of doing that… The activity of writing

that seems to me ok. I write things like that. But the activity of

getting people together and rehearsing them to make that into a reality, I don’t

have the chops for it in a certain sense. I want it to be more of a

circus. I’m decadent enough. I’ve been corrupted enough that I still

want that circus. But it bothers me. It bothers me because I think

maybe I lack the courage to escape the circus aspect of the theater.

NF: Have you ever thought of theater from

the perspective of either a written or oral tradition; how often are your texts

picked up and done by others?

RF: More and more people are doing

that. I make all of my raw material available on my web site. All of

my notes. There’s been a definite increase each year in the number of

people that pick up on that. But my plays are out there and I am convinced

– maybe not the last two years; my plays have been so minimal in terms of

language – but from 1980 through 1996 or 7, in my deluded way, I’m absolutely

convinced that some people will realize that these are great plays, these are

great texts. And I think of myself as operating specifically in the

tradition of Moliere and would hope that some years from now, people would pick

up on that and do them. And people do do them. Not in huge

numbers. But I think of myself, certainly up until the things I’ve done in

the last two years or so, as definitely continuing in the tradition of Western

written theater.

NF: If you picked up an old play of yours,

would you be coming to the same production choices as when you first did

it?

RF: That’s hard to say, because I don’t want

to do my old plays because I have new material that I’d rather do. But

people suggest that I do my old plays. Maybe someday I will. But

until I do it I won’t know.